The researchers shed light on the immune cells‘ capacity to collectively migrate through diverse environments in their work, which was published today in Science Immunology.

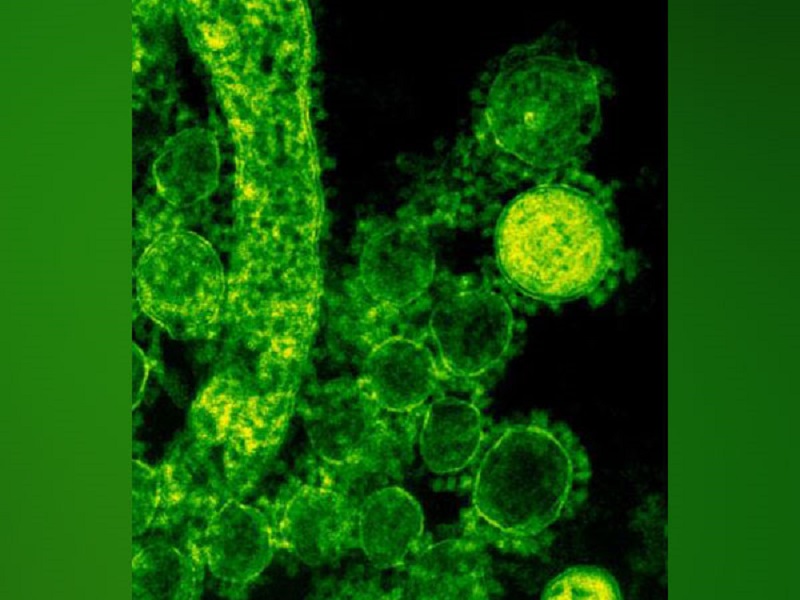

One of the major participants in our immune response is dendritic cells (DCs). They serve as a link between the adaptive response, which is a delayed response that targets very specific bacteria and builds memories to fight off future infections, and the innate response, which is the body’s initial response to an invasion. DCs search tissues for intrusions like detectives. They are triggered when they find an infection site and travel right away to the lymph nodes, where they transfer the combat strategy and start the subsequent phases in the cascade.

Chemokines, which are tiny signaling proteins produced by lymph nodes and create a gradient, direct their migration towards the lymph nodes. It was originally thought that DCs and other immune cells move towards a higher concentration in response to this extrinsic gradient. However, a recent ISTA study casts doubt on this assumption.

The surface feature known as “CCR7” that is present on activated DCs was closely examined by the researchers. The crucial role of CCR7 is to bind to the CCL19, a lymph node-specific molecule, which sets off the subsequent stages of the immune response.

”We found that CCR7 not only senses CCL19 but also actively contributes to shaping the distribution of chemokine-concentrations”>chemokine concentrations,” Jonna Alanko, a former postdoc from the lab of Michael Sixt, explained.

They showed through various experimental methods that chemokines are taken up and internalised by migrating DCs via the CCR7 receptor, leading to a local reduction of chemokine concentration.

They progress into higher chemokine-concentrations”>chemokine concentrations because there are fewer signalling molecules present. Immune cells can produce their own guidance cues thanks to their dual function, which improves the coordination of their group migration.

Together with theoretical physicists Edouard Hannezo and Mehmet Can Ucar from ISTA, Alanko and colleagues developed a quantitative understanding of this mechanism at the multicellular scale. They developed computer simulations that could replicate Alanko’s studies using their knowledge of cell dynamics and mobility. With the use of these simulations, the researchers hypothesised that the migration of dendritic cells is influenced by both the density of the cell population and individual responses to chemokines.

”This was a simple but nontrivial prediction; the more cells there are the sharper the gradient they generate—it really highlights the collective nature of this phenomenon!” said Can Ucar.

Additionally, the researchers found that T-cells—specific immune cells that destroy harmful germs—also benefit from this dynamic interplay to enhance their own directional movement. “We are eager to find out more about this novel interaction principle between cell populations with ongoing projects,” the physicist continued.