It is an age of disruption. At a time when the disruption has caused innovations in multiple sectors with information technology (IT) on the frontline, it has caused sweeping impacts on how we deal with regular work and chart out future courses. The disruption is evidently a deviation from past norms, values, and a mode of operation.

The utmost convenience caused by IT at times lands us in chaos. We have no option, but to internalize and adapt to the changes by leveraging its advantages and curbing the downsides. As new problems and norms are created, challenging the old ones, there are hardly any sectors left untouched.

The emergence of new problems with the changed modus operandi can be managed with the same old and traditional measures and rules or require new vision and legal measures are a burning debate at present. Though the previous measures are undoubtedly the foundations, the revision and correction are urgent so that the evolving issues ushered by IT can be addressed, a robust system ensured and law and order maintained.

Like many others, Nepal is also scrambling on how it can best deal with the digital sphere/cyberspace to protect and promote human rights and prevent digital harms. One of the challenging tasks is making proper laws and building relevant capacity on it.

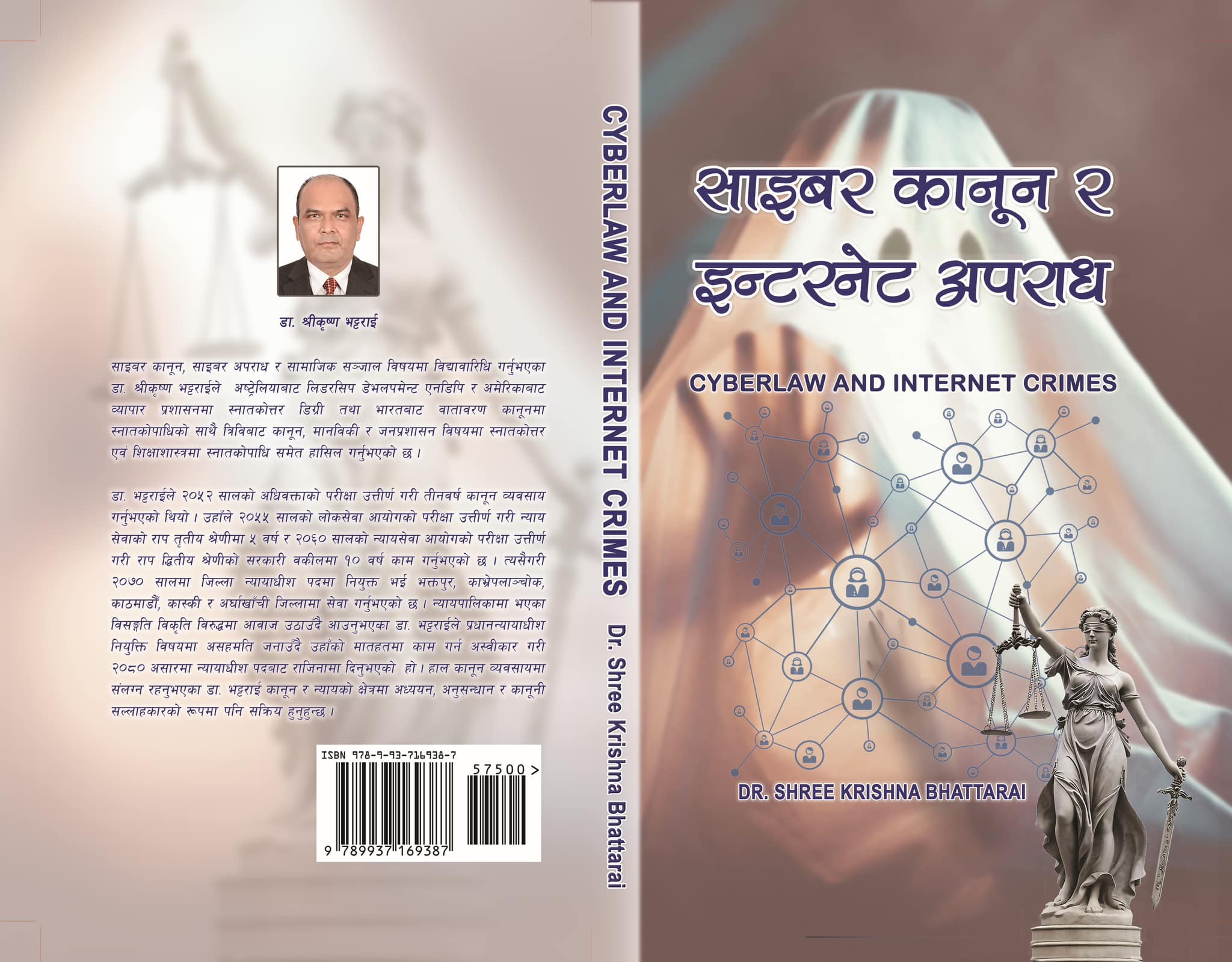

A research-based book written by Dr Shree Krishna Bhattarai, ‘Cyber Law and Internet Crimes’ is such text that explains many of such issues, thereby contributing significantly to the techno-legal governance in Nepal.

The book, the first of its kind, dwells thoroughly on issues such as cyber security, internet crimes, and cyber/digital safety which are already abuzz in Nepal as well because a huge number of people, especially the youths are online today. Digital gadgets are appendages- at home, at offices. On the other hand, the cyber indents are growing in recent years drawing all sides’ concern that even the parliaments began mulling laws relating to the regulation of cyberspace/digital sphere. But how are our legal initiatives so far on coping with the techno-legal issues? The national and international legal approaches and practices to address cyber incidents and cybercrimes are other salient features of the book.

The author has also shown the flaws in the legal arrangement at home, which are worth noting. It is not clear whether some cyber incident is just a misuse of social networking site or a cybercrime, we hurry to dub it a cybercrime and even go for lodging a case. What makes a crime a cybercrime must be understood well before chasing anyone under it. Interestingly, the Electronic Transaction Act (ETA) has been taken as the cure-all to deal with cyber incidents, to which the writer Dr Bhattarai argues the ETA is insufficient to sort out the legal issues of cyberspace. Similarly, the ETA has been decried by the freedom of expression advocates for a long, reasoning that it has been grossly misused to stifle free speech on digital sphere/cyber.

In addition to ETA, author Dr Bhattarai has mentioned well on other laws and draft bills keeping into account the provisions they have regarding cyber and digital rights.

The book written by Dr Bhattarai, who is the only Nepali scholar doing PhD in cyber law and cybercrime, has extensively defined and described cybercrimes and how they are perceived and legally settled in the country and abroad. The forms and types of cybercrimes and misuse of social networks are meticulously presented in the book. Dr Bhattarai who worked in the government legal service for 15 years, including the position of judge at district court and high court, honed his knowledge with his higher studies in the US and Australia. His legal career on the one hand and the passion to earn erudition in one of the pressing frontiers of modern time – the IT and cyber- have enriched the book contents.

The author has made us cautious that cyberspace/digital sphere/internet crimes are evolving sectors where studies are being conducted not only in a certain country but in the entire world owing to their nature and scope. He mentioned, “Research and investigation are going on across the globe on what sort of cyber laws are there to address the social network problems, crime and online defamation, and how these laws are applied. How are the cases filed in the courts across the world? Are these cases investigated and prosecuted by the State, thereby being subjected to criminal offenses or individual cases, getting complaint letters registered at court?” This is a stark reminder that the progressive nature of cyber sphere and mode of crimes warrant continuous update, study and engagement.

Similarly, the book provides measures for us to maintain digital safety. From using credible anti-virus to reducing unnecessary digital footprints, the author suggests us controlling GPS tracking setting, avoiding communication with unknown persons, not sharing personal information like phone number, habits, password and date of birth, and details on relatives on social networks, a strong password, and travel plans and photos. Some with intention, while many with innocence are acting in a way that results in sheer misuse of social networking sites or crimes. The digital safety tips are therefore important here.

The cases of internet crimes brought forth here from different countries are equally worth reading. In addition to Nepal’s cases, the book has brought forth examples from the cases and adjudication in Australia, India, and the UK. In a case (Heather Reid Vs Stan Dukic) relating to slander over Facebook, an Australian court ordered compensation for loss and ‘aggravating damage’ as well.

Another significant case is- a historic court decision (Shreya Singhal vs. Union of India) on a Facebook post- a defamation case- which reiterated the legislative intent, and not only added a dimension on Article 19 of the Indian constitution but also influenced heavily on the internet use, the author Dr Bhattarai claimed.

In the UK, the Supreme Court explained ‘serious harm test’- how it is dealt with in interpretation and behaviour. “While defining a defamatory statement, the court decided on checking whether the statement has caused serious harm or is possible to cause it.”

Overall, the book has underlined the urgency of capacity building in investigation, prosecution and adjudication relating to the cases of cybercrime. Whether they are police persons or attorneys or judges who are directly involved in the legal proceedings of tech crimes or general people and those involved in research, advocacy, media and academia, the book is rich in resources that help equip them with modern knowledge. It has paved way for techno-legal governance in Nepal, which is a new but fascinating regime.

At a time when information technology has prevailed in every aspect of life, people’s behaviour needs to be observed minutely from social, economic, technological and legal angles. But, the dearth of techno-legal resources to deal with the digital and tech issues surrounding human behaviour is a sheer hindrance to adjudicating justice. The book written in the initial phase of tech deluge in Nepal will undoubtedly fill the legal gaps. It is a must-read text to know the evolving tech regime and ensure digital justice.

The book is published by the Bagmati Province Government, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Law, Communication Registrar’s Office. It costs Rs 750.