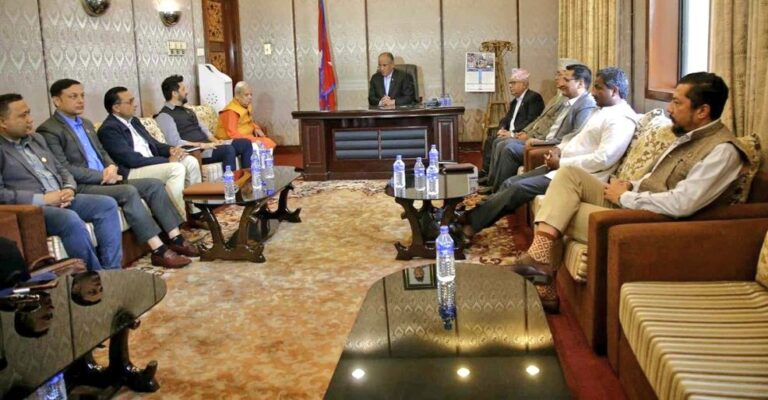

Nepal’s two largest parties, the Nepali Congress (NC) and the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist–Leninist (CPN-UML), have formed an alliance, with UML Chairman KP Sharma Oli serving as Prime Minister.

The key agenda of this alliance includes amending the constitution, maintaining political stability, controlling corruption, and promoting good governance.

The formation of a government or alliance by the largest and second-largest parties in the House of Representatives is rare in democratic nations unless absolutely necessary, during national emergencies, or for specific tasks over a certain period.

This is not the first time Nepal’s largest parties, the Nepali Congress and the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist–Leninist (CPN-UML), have shared power.

They have cooperated in government six times before, beginning with the 1990 People’s Movement. However, their collaboration was generally limited to interim governments, constitution drafting, and holding elections.

The current power-sharing agreement between the Congress-UML alliance occurred after the second election of the Constituent Assembly, with the primary agenda being to ensure the timely promulgation of the constitution, following the failure of the first Nepalese Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution. The first assembly was dissolved on May 28, 2012.

Over time, other parties, including the UML, have joined the call for constitutional amendments. There is growing consensus that the Constitution must be amended immediately, as some provisions have become significant obstacles to delivering meaningful results for the people.

Despite the current government’s public emphasis on the necessity of the alliance, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli’s recent statement on constitutional amendment has raised doubts about the government’s intentions.

It suggests that the alliance may primarily be motivated by the desire to maintain government control and power-sharing, rather than being genuinely committed to the public objectives they have reiterated many times over.

Even if the current ruling coalition genuinely intends to amend the constitution, it lacks the necessary majority and has failed to build a broader political consensus that includes all parties and stakeholders.

Due to growing political divisions and increasing public frustration, the coalition is unable to secure the two-thirds majority required for constitutional amendments.

Many view this frustration as a ticking time bomb, with new voters potentially shifting their support to other parties in the next elections.

Both the UML and the Nepali Congress could face setbacks in the future, making it challenging for them to secure the two-thirds majority needed in both houses of the Federal Parliament and the provinces for a constitutional amendment.

Following the Congress-UML coalition, the issue of amending the constitution has ignited widespread debate.

While some consider it absolutely necessary, others view it as a Pandora’s Box for Nepal, given the country’s past negative experiences and the deep political divisions that still exist.

Although the question of constitutional amendment has resurfaced in Nepal’s political discourse, the true motives of the current government remain increasingly uncertain.

Amending the country’s nine-year-old constitution is not an easy task due to practical, technical, political, and several other challenges. The current political scenario suggests that power-sharing within the government may be limited, rather than following the agenda-driven approach the coalition initially proposed.

The formation of a three-tier political mechanism—at the center, in the provinces, and in the districts—by the two parties has further fueled doubts about their intentions.

This mechanism was designed to facilitate the governance of the Nepali Congress and the CPN-UML at the center while resolving disputes at the provincial and district levels.

However, it is largely seen as an effort to consolidate power, rather than focusing on the key priorities of government formation and other pressing agendas.

Prime Minister KP Oli’s latest remarks have almost closed the chapter on constitutional amendment efforts in the near future, at least before the upcoming elections.

Five months after the government was formed under his leadership, coalition partners Nepali Congress and CPN-UML are preparing to establish separate mechanisms within their parties to identify areas for constitutional amendments.

However, these efforts appear more symbolic than substantive, as the top leadership seems to have little intention—or hope—for the amendment process to move forward.

While the amendment process may eventually involve bilateral talks between the ruling coalition of Congress and UML, their serious initiation of the amendment process seems unlikely following the latest statement from the Prime Minister.

What the Congress-UML Coalition Promised and the Agenda Before Forming the Government

Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli, while seeking a vote of confidence in the House on July 21, 2024, updated the House on the seven-point agreement reached on July 1, 2024, between the first and second-largest parties in the House of Representatives. The following are the seven points in the agreement that the PM shared with the House:

What is the Constitutional Provision for Constitutional Amendment?

Nepal’s Constitution of 2015, in Part 31, Article 274, outlines the procedure for amendments, requiring a two-thirds majority in Parliament.

The Constitution includes provisions for review and amendment every 10 years, with a clause allowing flexibility, as all articles, except Article 274(1), are amendable.

In the case of provincial readjustment, a two-thirds majority from the provincial assemblies is also required.

The amendment bill must be endorsed by both the House of Representatives and the National Assembly, and then authenticated by the President before it can come into effect.

Part 31 of Nepal’s Constitution of 2015 specifically outlines the procedure for the amendment of the Constitution, following the process established therein.

(1) This Constitution shall not be amended in way that contravenes with self-rule of Nepal, sovereignty, territorial integrity and sovereignty vested in people.

(2) Except for matters under clause (1), in case an amendment is sought in matters that fall under the fundamentals of this constitution, such a proposal shall be presented to either house of the federal legislature.

Provided that, Clause (1) shall not be amended.

(5) Pursuant to forwarding the bill to the Provincial Assembly as provided in Clause (4), the Provincial Assembly shall have to get the consensus bill endorsed or rejected through majority of the Provincial Assembly and forward the information regarding the same to the federal legislature, within three months.

Provided that, In case the Provincial Assembly is not in place, the bill shall have to be endorsed or rejected within three months from the time the assembly comes into force and forward the information to the federal legislature.

What Are the Issues and Demands of Constitutional Amendment?

The agenda of amending Nepal’s Constitution has been ongoing since its promulgation. This issue has been a recurring topic, with the Constitution having already been amended twice on different matters.

Before addressing further amendments, it is crucial to clarify whether the government was formed merely based on an arithmetic majority or with a genuine focus on ensuring stability.

Initially, the CPN-UML resisted discussions on constitutional amendments or any related issues.

However, major political parties now acknowledge the need for changes, arguing that certain provisions in the Constitution have contributed to political instability or have led to an out-of-control political status quo.

Instead, they focus on controlling institutions like the judiciary, constitutional bodies, and parliament, which undermines the principle of separation of powers.

Nine years have passed since the promulgation of Nepal’s new constitution, during which two elections (in 2074 and 2079) have taken place.

Throughout this period, the necessity of amending specific provisions of the Constitution has become increasingly evident.

During the implementation of the Constitution, certain provisions—such as the electoral system, the number of representatives, and the government formation process—have contributed to political instability.

Over time, other parties, including the UML, have joined the call for constitutional amendments. There is growing consensus that the Constitution must be amended immediately, as some provisions have become significant obstacles to delivering meaningful results for the people.

Constitutional amendments require a high level of understanding among top leadership and consensus among all political parties, ensuring their confidence and participation in the process.

The issue of constitutional amendments will not only concern domestic factors or demands; it will also be intertwined with geopolitical dynamics.

Any steps toward amending the Constitution require caution, maturity, and extensive discussion to ensure maximum ownership for its long-term stability and functionality.

Major political parties and their leaders have primarily emphasized modifying the electoral system, particularly focusing on proportional representation and raising the threshold required to qualify as a national political party.

Smaller political parties, while also advocating for constitutional amendments, have a distinct set of priorities.

The demands for constitutional reform are wide-ranging, including electoral reforms, judicial system reforms, reinstating Nepal as a Hindu state, introducing a directly elected executive head, restructuring provinces, and ensuring proportional representation.

If the constitutional amendment process gains momentum, it is certain that many more ideas and demands will surface in public discourse and potentially lead to agitations on the streets, contributing to a richer debate and influencing the trajectory of reforms.

Despite an agreement between the Nepali Congress and CPN-UML, the delay in the proposed constitutional amendment process has sparked suspicions about the true intentions of the government and the two leading parties.

It is essential to understand that the process of amending and reviewing the Constitution transcends the immediate political gains or losses of individual parties; it is fundamentally connected to the core identity and aspirations of the nation.

Political Complacency Derails Nepal’s Constitution in Real Implementation

Nepal’s constitution is not flawless and reflects political compromises made during the Constituent Assembly (CA) process.

The Constitutional Bench has failed to deliver significant verdicts in recent years. Proper interpretation of the constitution is vital to its implementation by the Supreme Court, but the lack of decisive rulings weakens its essence.

While its weaknesses can be addressed through amendments, political parties and leaders lack the will to do so.

Instead, they focus on controlling institutions like the judiciary, constitutional bodies, and parliament, which undermines the principle of separation of powers.

Constitutional bodies suffer from politicization, loyalist appointments, and dysfunction.

Political parties have failed to review the constitution or assess their role in its implementation. A lack of determination and clear direction continues to stall any progress.

Frequent government changes, economic crises, corruption, unemployment, and poor governance have frustrated citizens day by day.

Public trust in the government has eroded, and many have lost hope in the nation’s future. Youth are leaving for abroad, while those remaining in Nepal grow increasingly disheartened.

People are frustrated with the government’s failure to deliver results. The rule of law is being undermined, economic issues remain unresolved, and citizens feel no connection to or ownership of the constitution.

A constitution is merely a tool, not a solution; its success depends on political parties changing their ways and ensuring its proper implementation.

Provincial governments in Nepal remain overly dependent on the central government and political parties for funding and decision-making, undermining the spirit of federalism.

While the federal system was designed to decentralize power and grant greater autonomy to provincial and local governments, in practice, the central government and top leaders continue to exert significant control over provincial affairs.

This excessive intervention hinders the true potential of federalism as well as the trust of provincial authorities.

The federal structure, which was intended to empower provincial governments to make independent decisions, has instead been stifled by centralized party interference.

Under the federal structure, the shadow of the central government and leaders looms large, preventing provincial governments from exercising true authority. Provincial governments are unable to govern with the autonomy they were meant to have.

While the federal structure has created opportunities for local leaders to better represent their constituencies, their effectiveness is undermined when the central government overrides their authority.

Supreme Court Credibility at Stake: Growing Doubts Over Constitutional Bench’s Performance

The Constitutional Bench of Nepal’s Supreme Court, established as mandated by the constitution, has recently been seen as ineffective.

Legal practitioners argue that this provision should be amended to avoid potential moral conflicts when the court hears cases in the Constitutional Bench related to appointments made by the Constitutional Council.

The Constitutional Bench has failed to deliver significant verdicts in recent years. Proper interpretation of the constitution is vital to its implementation by the Supreme Court, but the lack of decisive rulings weakens its essence.

Interpretation of complex constitutional cases breathes life into a constitution, but Nepal’s Supreme Court, tasked with interpreting it correctly, has repeatedly fallen short.

Dozens of constitutional cases, including those related to the 52 constitutional appointments, the jurisdiction of federal, provincial, and local governments, and election disputes, remain pending. When these cases will be heard remains uncertain.

The judiciary’s decline accelerated following the appointment of Cholendra SJB Rana as Chief Justice. Rana’s rampant corruption in the judiciary and his appointment of non-credible, unqualified, and non-performing judges severely damaged the judiciary’s image and public trust.

On February 13, 2022, an impeachment motion was filed against Rana for failing to fulfill his official responsibilities, resulting in his immediate suspension. Despite his removal, it has taken years for the judiciary to recover.

Since Rana’s suspension, four Chief Justices have failed to restore the credibility of the judiciary and the Constitutional Bench’s effectiveness in addressing significant cases.

The current Chief Justice, Prakash Man Singh Raut, faces a crucial test of his credibility in handling critical cases, such as the long-pending issue of the 52 constitutional appointments.

Filed four years ago, this case has been deferred 36 times. The next hearing is scheduled for January 15, 2025.

The 52 constitutional appointments were made during Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli’s tenure.

On December 15, 2020, then-Prime Minister Oli held a Constitutional Council meeting without Speaker Agni Prasad Sapkota and opposition leader Sher Bahadur Deuba.

The same day, the government introduced an ordinance enabling the Council to make decisions by a majority of its permanent members, bypassing the usual process and fueling the ongoing legal challenge.

The outcome of this four-year-old case will be a critical test of Nepal’s Supreme Court’s credibility and the judiciary’s ability to uphold the constitution.

The Nepal Bar Association has raised concerns about the need for constitutional amendments to strengthen the judiciary through judicial reform.

The Nepal Bar Association has endorsed the proposal from its national conference for a constitutional amendment.

The proposal highlights the need for restructuring the judiciary and the Judicial Council, further empowering it, providing a dedicated Constitutional Bench, and ending the provision of holding a Supreme Court judge in the same office for too long.

Nepal’s limited resources make it nearly impossible to ensure the fulfillment of all fundamental rights enshrined in the constitution. The absence of operational mechanisms and supporting laws further hinders their implementation.

Lawyers and judges have pointed out key provisions that require change, such as the representation of the Chief Justice in the Constitutional Council and the structure of the Judicial Council. The Bar Association is advocating for the removal of the Chief Justice’s representation in the Constitutional Council.

Legal practitioners argue that this provision should be amended to avoid potential moral conflicts when the court hears cases in the Constitutional Bench related to appointments made by the Constitutional Council.

Nepali Constitution: Provisions Remain Promises on Paper, Lacking Functional Delivery

The Constitution of Nepal, 2015, was promulgated with lofty promises and aspirations but lacks functional implementation.

While the constitution guarantees various rights, it has failed to ensure that these guarantees go beyond words on paper to become a reality for all Nepali citizens.

Article 47 of the constitution mandates the government to enact laws for implementing fundamental rights within three years of its promulgation.

However, several rights outlined in Articles 16 to 46, which guarantee citizens’ fundamental rights, remain unrealized.

One such guarantee is the inclusion of several basic rights as fundamental, but these provisions remain largely theoretical and lack practical implementation.

The constitution recognizes various social, economic, and cultural rights, such as the rights to food, shelter, health, and education, aiming to achieve socialism, social justice, and inclusive development. However, these goals have not been fully realized in practice.

Fundamental rights such as job security, access to clean drinking water and sanitation, social justice, socialism, equitable economic development, and the right to live with respect, liberty, and dignity remain elusive for the masses.

Nepal’s constitution adopted a three-tier government structure with a federal framework, but this arrangement has led to friction between the three levels of government.

Nepal’s limited resources make it nearly impossible to ensure the fulfillment of all fundamental rights enshrined in the constitution. The absence of operational mechanisms and supporting laws further hinders their implementation.

The Nepali Constitution guarantees more rights than those of many developed countries, even protecting job rights.

It promises a broad range of rights. While these provisions are commendable on paper, their implementation remains a challenge.

Although significant social progress can be seen in consultations, in practice, most of these rights and constitutional provisions are not being effectively enforced.

The constitution has also failed to deliver the economic prosperity and development that political leaders promised. Without the necessary regulations in place, fundamental rights and constitutional provisions cannot be fully realized, leaving the aspirations of the constitution unfulfilled and rendering it increasingly nonfunctional.

Calls to Reform Nepal’s Costly and Ineffective Electoral System Gain Momentum

Nepal’s electoral system has become one of the most expensive in the region, raising concerns about its sustainability and fairness.

Despite being a small country, Nepal has a disproportionately high number of people’s representatives and authorities, which adds to the financial burden on the nation.

As Nepal grapples with growing domestic and foreign debt, along with severe economic challenges since transitioning to a federal democratic republic, public frustration is mounting over the current political system.

Key economic indicators—such as exports, gross domestic product, trade deficit, tax revenue, national debt, and manufacturing—have all seen rapid declines, signaling a tipping point for the country’s economy.

In such circumstances, remittance money from Nepali citizens working abroad has become a lifeline for the public, sustaining livelihoods and keeping the economy afloat.

Currently, Nepal is operating under a costly mixed electoral system, combining direct and proportional representation.

At the federal level, 60% of the elections are direct, and 40% are proportional. In the 275-member House of Representatives, 165 seats are filled through direct elections, while 110 are allocated proportionally.

Similarly, the seven provincial assemblies collectively comprise 550 seats, with 330 directly elected representatives and 220 chosen through proportional representation.

Additionally, the National Assembly consists of 59 members. Altogether, there are 884 MPs across the federal and provincial levels.

This costly system has created significant barriers for honest leaders and those without substantial financial resources to participate in elections.

The proportional system, designed to promote inclusiveness, has also become a subject of controversy, as it has been misused by top leaders.

The Constitution establishes 13 constitutional commissions, but apart from a few, many have not played an effective role. In some cases, these commissions have become little more than centers for recruitment.

Nepotism within political parties is growing, as party lists are filled with relatives and close associates of influential leaders, undermining the core principles of inclusiveness and democratic values.

This growing dissatisfaction with the proportional system could serve as a critical basis for future constitutional amendments.

Strained Relationship Between Union, State, and Local Governments in Nepal’s Federal Structure

Nepal’s constitution adopted a three-tier government structure with a federal framework, but this arrangement has led to friction between the three levels of government.

Part 20 of the Constitution outlines the interrelationship between the Union, Province, and Local levels.

Despite two elections having taken place since the Constitution’s promulgation, coordination problems between the three levels persist, with jurisdictional disputes remaining unresolved.

While the relationship between the Union, Province, and Local levels is intended to be based on cooperation, coexistence, and coordination, complaints have consistently arisen from the state and local levels.

These complaints revolve around the central government’s failure to pass laws, delegate authority, send staff, and facilitate tax collection.

There have been instances where local and state governments have asserted claims to rights that they believe are theirs by virtue of the Constitution.

At the local level, some representatives have even started to refer to themselves as ‘kings,’ reflecting dissatisfaction with the central government.

The frequent changes in coalitions within the provinces have led to frequent changes of provincial Chief Ministers and Ministers, resulting in instability and inefficiency.

The actions of the government at all three levels have led to public resentment and discontent. Although the Constitution provides for an Inter-Provincial Council, it has rarely convened, limiting its impact.

According to constitutional law experts, the issue of constitutional amendment is closely tied to the relationship between the Union, Province, and Local levels.

Frequent Government Changes Demand Constitutional Amendment

Article 76 of the Constitution outlines the formation of the Federal Government’s Council of Ministers, while Article 168 provides for the formation of the Provincial Council of Ministers.

Since the promulgation of the Constitution, two elections have been held, but frequent changes in government have occurred at both the federal and provincial levels.

The provisions of the Constitution are being interpreted and, at times, misinterpreted, creating confusion and instability.

The implementation of the Constitution, particularly regarding the coalition process within the government, has proven problematic.

During the 73-year history of constitutional development, Nepal has experienced seven constitutions in over seven decades, each reflecting different political systems.

Given these challenges, it appears necessary to amend the Constitution to ensure greater stability in governance.

Questionable Effectiveness of Constitutional Commissions Raises Calls for Constitutional Amendment

The Constitution establishes 13 constitutional commissions, but apart from a few, many have not played an effective role. In some cases, these commissions have become little more than centers for recruitment.

Part 21 covers the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority, Part 22 addresses the Auditor General, Part 23 discusses the Public Service Commission, Part 24 deals with the Election Commission, Part 25 outlines the National Human Rights Commission, and Part 26 addresses the National Natural Resources and Finance Commission.

Additionally, Part 27 includes seven other commissions: the National Women’s Commission, National Dalit Commission, National Inclusion Commission, Tribal Tribes Commission, Madhesi Commission, and Muslim Commission.

However, the effectiveness of several of these commissions has been called into question. Given these concerns, there may be a need to amend the Constitution regarding the role and functioning of these commissions.

Criticism Grows Over High Number of Representatives, Calls for Reduction Through Constitutional Amendment

Nepal currently has 753 local levels, a number considered quite large. While the size of the local levels has made the three-tier government structure more effective, it has also led to distortions.

Despite efforts to centralize at Singha Durbar, local levels have struggled to provide efficient service delivery.

The District Coordination Committee has also failed to play a significant role and may be reconsidered for removal.

There have been discussions, particularly between Congress and UML, about reducing the number of local levels and increasing the number of wards. This proposal has been met with a positive outlook.

There are 884 members in the House of Representatives, the National Assembly, and the State Assembly. Given Nepal’s small size, there is growing criticism that the number of representatives is excessively high.

Some view the provincial structure as a hindrance to national unity. Calls are being made for a constitutional amendment to reduce the number of representatives in the House of Representatives, National Assembly, and Provincial Assembly.

Vice President Role Seen as Ineffective

The role of the Vice President in Nepal is currently seen as ineffective, with calls being made to transform the position into the Speaker of the National Assembly.

Constitutional experts suggest that the Vice President could take on the role of the President of the National Assembly.

Additionally, there are discussions about reducing the number of proportional members in the House of Representatives and converting them into national members.

Following the UML-Congress alliance, the public expected improvements in service delivery, good governance, and constitutional amendments, but nothing materialized.

Some also advocate for the House of Representatives to be made entirely direct, further reshaping the political structure.

The Journey of Nepal’s Constitution: From the Rana, Royal to Democracy, and the Constituent Assembly

During the 73-year history of constitutional development, Nepal has experienced seven constitutions in over seven decades, each reflecting different political systems.

The current constitution is the first to be written by a Constituent Assembly elected by the citizens of Nepal.

Nepal adopted its first constitution on 26 January 1948 under Rana Ruler Padma Shumsher.

After the democratic revolution of 1951, King Tribhuvan promulgated another constitution on 11 April 1951.

The Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal, 1959, was then promulgated on 12 February 1959. In 1961, King Mahendra overthrew the democratically elected government, introducing an absolute monarchy with a partyless Panchayat system through the promulgation of a new constitution on 16 December 1962.

The people’s movement of 1990 led to the Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal, 1990, which lifted the ban on political parties.

In 2006, following a protest movement by the seven-party alliance, the Interim Constitution of Nepal was promulgated in 2007.

The first constituent assembly elections were held in 2008 but failed to promulgate a constitution.

This was followed by the second constituent assembly elections in 2013, which culminated in the promulgation of Nepal’s new constitution in 2015, replacing the Interim Constitution of 2007.

The new constitution reflects the Maoists’ demands, fulfilling the goals of their 10-year insurgency that ended with the 2006 peace deal.

This led to the establishment of a Constituent Assembly tasked with drafting a new constitution and abolishing the 240-year-old monarchy.

The Madheshi and Maoists’ federalism proposal was later adopted by mainstream parties like Nepali Congress and UML, as well as smaller parties.

Nepal’s latest constitutional process has been one of the most expensive and intensive in the world, encompassing the cost of elections to two Constituent Assemblies, each with 601 members, and totaling over $400 million in expenditures.

Conclusion: Constitutional Amendments Are Essential; Failing to Address Key Issues Could Lead to a Breakdown of the Current System

Despite the two largest parties, Nepali Congress and UML, joining forces to form the current government, it is headed in the wrong direction, straying from key agendas and promises.

The public initially believed the coalition would open new opportunities, but nothing has materialized along the right track or according to their previous seven-point commitments.

One key issue that brought these two major parties together is the need for a constitutional amendment.

However, if they fail on this front, the foundation of the coalition will collapse. Many provisions of the constitution require amendment, and if political behavior doesn’t change, the coalition might face instability within a few months, possibly leading to another shift aimed at diverting public attention.

If politics remain off track and the situation grows hopeless, it could trigger a new chapter of political turmoil and instability that could pose a serious threat to the current political system.

After nearly six months, it has become clear that amending the constitution is not as straightforward as they promised.

The government’s performance in key areas, especially economic progress and good governance, has been dismal.

Following the UML-Congress alliance, the public expected improvements in service delivery, good governance, and constitutional amendments, but nothing materialized.

Hopes for faster, more efficient, and less time-consuming services were met with delays and empty speeches from the governing leaders.

Management systems are becoming increasingly inefficient and disorganized. Recent government actions are widely seen as political vengeance, while good governance, effective administration, and streamlined management are crucial for the public, not the hollow rhetoric of leaders claiming fake progress.

In a democratic society, adherence to regulations and systems is crucial. Laws, rules, and regulations are essential for accomplishing tasks.

However, deep-rooted corruption, delayed service delivery, obstacles for service seekers, unnecessary documentation, and sluggish workflows are severely hindering productivity in many government offices.

The government has failed to implement effective strategies to address key issues, further fueling public frustration, which is now reaching a tipping point.

Nepali politics has long been fragile and unstable. National agenda-based politics are often difficult to pursue due to growing political inconsistency, shifting ruling coalitions lacking ideological coherence, a focus on power-sharing, and opportunistic approaches that can sway either way depending on the parties’ bargaining or benefits.

Any miscalculation of the current situation will not only impact the government or coalition but the entire political system and the nation as a whole.

Parties like the Maoists, RPP, RSP, Madhesi, and other factions are preparing for street protests, mass gatherings, and displays of force.

Geopolitics also significantly impacts Nepal’s political landscape. In the past two years, multiple high-profile scams, scandals, and corruption cases involving leaders from major political parties have emerged.

Various forces are exploiting this growing anger and frustration of the citizens. People prioritize services, jobs, and economic opportunities over the constitution itself.

Doubts about its sustainability and core principles are rising like never before. Addressing anti-constitution sentiments requires effective governance and decisive action from political leaders.

Nepali society has become deeply polarized. Many members of traditionally marginalized groups fear that the constitution will continue to work against them, while royalists view the failure of this constitution as an opportunity for a comeback.

If the ruling Congress-UML strays from key agendas in the 7-point agreement that shaped its formation, it could further deepen political fractures.

The constitution has proven to be less realistic and aspirational than envisioned.

If politics remain off track and the situation grows hopeless, it could trigger a new chapter of political turmoil and instability that could pose a serious threat to the current political system.

For many years, Nepal’s politics has lacked true ideology, with power-sharing and tactical gains prevailing in the absence of clear political agendas, principles, or values.

As is characteristic of Nepali politics, it remains unpredictable, with frequent changes in political coalitions making it complex and unstable—often leading to a new prime minister nearly every year.

Since the 1951 revolution that overthrew the Rana dynasty, Nepal has experienced various political regimes, but no government has completed its full term.

Historically, Nepal has been politically unstable, and changes in government rarely eliminate leaders for long.

The only certainty in Nepali politics is uncertainty; the issues that trigger change cannot be predicted and are often marked by confusion that culminates in more dramatic confusion.

Nepal has become a world champion of political instability, and after over a decade of turmoil, things may change again in 2025.

If the current political situation continues on its divisive and uncertain path, it may reach a tipping point within a few months.

All major political parties must find ways to address their disagreements and underlying disputes.

If the confusion persists for a few more months, there is a clear risk of escalating protests and unrest.

Without compromise and good faith from all sides, Nepal could face an unforeseen political, economic, and constitutional crisis.

If the ruling Congress-UML strays from key agendas in the 7-point agreement that shaped its formation, it could further deepen political fractures.

This would lead to new divisions in the parliamentary mandate and extend the phase of instability.

If political instability continues, Nepal may face yet another sad chapter in 2025.