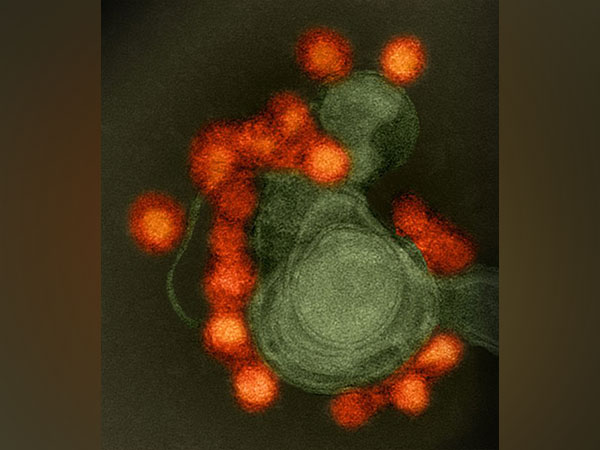

The Zika virus has a cunning plan. Once a virus has entered the body, it tends to head straight for dendritic cells, which are necessary for an efficient immune response.

According to LJI Professor Sujan Shresta, PhD, a member of the LJI Center for Infectious Disease and Vaccine Research, “Dendritic cells are key cells of the innate immune system.”

Why is this virus so crafty that it can infect cells that ordinarily fend off infections?

According to UC San Diego Professor Aaron Carlin, M.D., PhD, a former research assistant in the Shresta Lab and co-leader of the current study, “Understanding how viruses interact with human cells is crucial for understanding how to treat or prevent infection in the future.”

Emilie Branche, PhD, a former postdoctoral researcher at LJI, created a model to understand better how dendritic cells are targeted by dengue and zika viruses. She experimented with monocytes, which are human immune cells, and stimulated them to become dendritic cells.

Branche investigated the changes in gene expression that occurred in these dendritic cells after a dengue or zika infection. After that, she compared the gene expression alterations to those in cells that had had a “mock infection.” This comparison showed in detail how Zika manages to take over cells.

Scientists discovered that the Zika virus affects the genes in dendritic cells that regulate lipid metabolism. A cellular protein called SREBP is summoned by the virus, which causes lipid, or fat molecule, production to ramp up. These lipids served as the building blocks for the assembly of new Zika virus copies, copies designed to circulate throughout the body and propagate infection.

According to Branche, “We demonstrated that Zika, but not dengue, affects cellular metabolism to boost its replication.”

Following that, the group examined whether Zika converts additional cells into lipid factories. The researchers demonstrated that Zika does not alter the lipid metabolism genes in neural precursor cells, despite the fact that it is also known to target these cells. Shresta was taken aback to notice that these modifications were limited to dendritic cells and that Zika, as opposed to dengue, changed lipid synthesis.

Shresta comments, “These viruses are crazy.” It depends much on the virus and the cell type as to how these viruses alter host cell responses.

The following stage is to create antivirals that prevent Zika from using the genes involved in lipid metabolism. According to the latest study, therapeutically suppressing SREBP may be promising.

Dengue, a cousin of Zika: what should be done?

Shresta envisions an SREBP inhibitor as just one component of a “cocktail” of inhibitors to treat a variety of flavivirus illnesses due to how closely related and overlapping these viruses are.

The closer we get to a “pan-flavivirus” inhibitor, she claims, the more knowledge we can produce about these viruses.