They said communications intercepted by the National Security Agency in January showed that Iran’s Revolutionary Guard discussed mounting “USS Cole-style attacks” against the base, referring to the October 2000 suicide attack in which a small boat pulled up alongside the Navy destroyer in the Yemeni port of Aden and exploded, killing 17 sailors.

The intelligence also revealed threats to kill Gen. Joseph M. Martin and plans to infiltrate and surveil the base, according to the officials, who were not authorized to publicly discuss national security matters and spoke on condition of anonymity. The base, one of the oldest in the country, is Martin’s official residence.

The threats are one reason the Army has been pushing for more security around Fort McNair, which sits alongside Washington’s bustling newly developed Waterfront District.

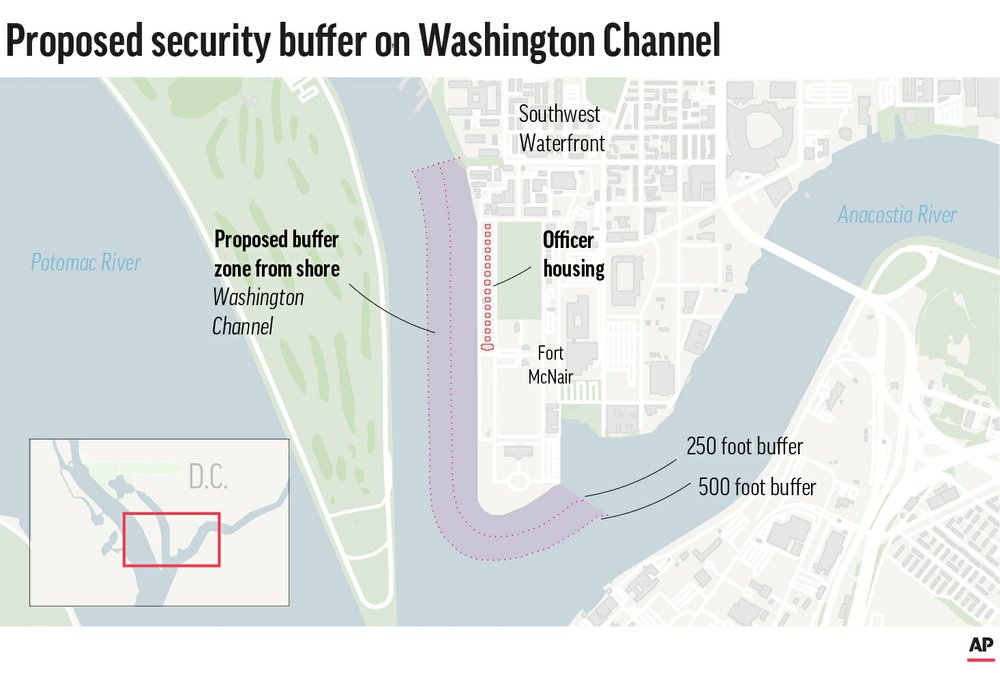

City leaders have been fighting the Army’s plan to add a buffer zone of about 250 feet to 500 feet (75 meters to 150 meters) from the shore of the Washington Channel, which would limit access to as much as half the width of the busy waterway running parallel to the Potomac River.

The Pentagon, National Security Council and NSA either did not reply or declined to comment when contacted by The Associated Press.

As District of Columbia officials have fought the enhanced security along the channel, the Army has offered only vague information about threats to the base.

At a virtual meeting in January to discuss the proposed restrictions, Army Maj. Gen. Omar Jones, commander of the Military District of Washington, cited “credible and specific” threats against military leaders who live on the base. The only specific security threat he offered was about a swimmer who ended up on the base and was arrested.

Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton, the district’s sole representative in Congress, was skeptical. “When it comes to swimmers, I’m sure that must be rare. Did he know where he was? Maybe he was just swimming and found his way to your shore?” she said.

Jones conceded that the swimmer was “not a great example there, but our most recent example” of a security breach.

He said the Army has increased patrols along the shoreline, erected more restricted area signs and placed cameras to monitor the Washington Channel.

Puzzled city officials and frustrated residents said the Army’s request for the buffer zone was a government overreach of public waterways.

Discussions about the Fort McNair proposal began two years ago, but the recent intelligence gathered by the NSA has prompted Army officials to renew their request for the restrictions.

The intercepted chatter was among members of the elite Quds Force of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard and centered on potential military options to avenge the US killing of the former Quds leader, Gen. Qassem Soleimani, in Baghdad in January 2020, the two intelligence officials said.

They said Tehran’s military commanders are unsatisfied with their counterattacks so far, specifically the results of the ballistic missile attack on Ain al-Asad airbase in Iraq in the days after Soleimani’s killing. No US service members were killed in that strike but dozens suffered concussions.

Norton told the AP that in the two months since the January meeting, the Pentagon has not provided her any additional information that would justify the restrictions around Fort McNair.

“I have asked the Department of Defense to withdraw the rule because I’ve seen no evidence of a credible threat that would support the proposed restriction,” Norton said. “They have been trying to get their way, but their proposal is more restrictive than necessary.”

She added: “I have a security clearance. And they have yet to show me any classified evidence” that would justify the proposal. Norton pointed out that the Washington Navy Yard and Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling, which also have access to district waters, do not have restricted zones along their shorelines and have not requested them.

The proposed changes, outlined in a Federal Register notice, would prohibit both people and watercraft from “anchoring, mooring or loitering” within the restricted area without permission.

The notice specifies the need for security around the Marine Helicopter Squadron, which transports American presidents, and the general and staff officers’ quarters located at the water’s edge. The southern tip of Fort McNair is home to the National War College, where midlevel and senior officers gunning for admiral or general study national security strategy.

The Washington Channel is the site of one of the city’s major urban renewal efforts, with new restaurants, luxury housing and concert venues. The waterway flows from the point where the city’s two major rivers, the Potomac and Anacostia, meet.

It’s home to three marinas and hundreds of boat slips. About 300 people live aboard their boats in the channel, according to Patrick Revord, who is the director of technology, marketing and community engagement for the Wharf Community Association.

The channel also bustles with water taxis, which serve 300,000 people each year, river cruises that host 400,000 people a year and about 7,000 kayakers and paddleboarders annually, Revord said during the meeting.

Residents and city officials say the restrictions would create unsafe conditions by narrowing the channel for larger vessels traversing the waterway alongside smaller motorboats and kayakers.

Guy Shields, a retired Army infantry colonel and member of the Capitol Yacht Club who opposes the restrictions around Fort McNair, said during the meeting that waterway restrictions wouldn’t boost security.

“Those buoys aren’t going to do anything to enhance security. It will increase congestion in an already congested area,” Shields said. “And I’ll say, signs do not stop people with bad intentions.”

It’s unclear whether the new intelligence will change the city’s opposition to the Army’s security plan.