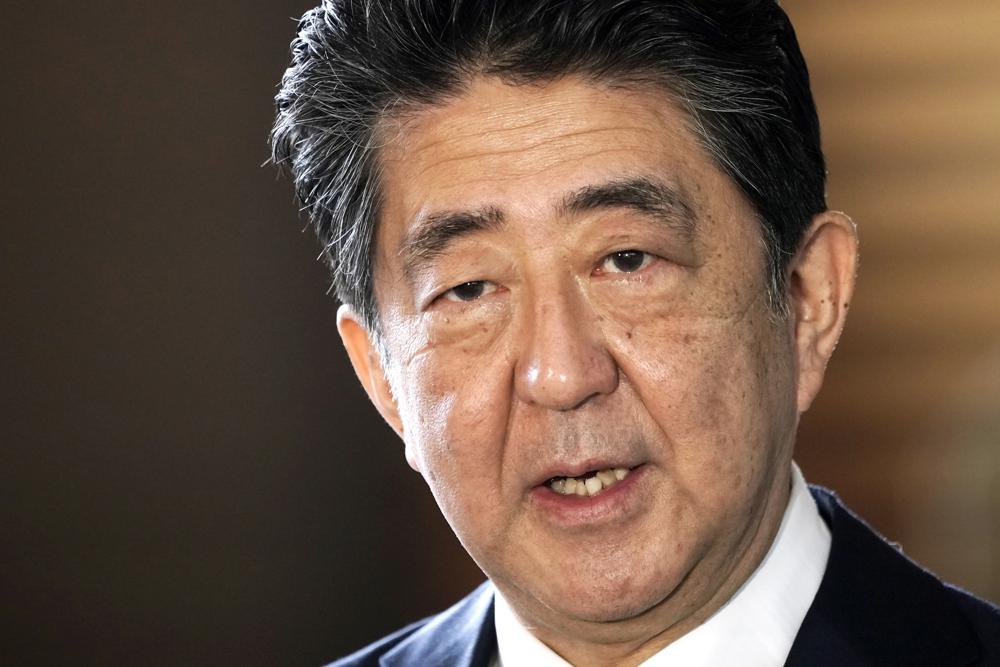

Assassinated former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was perhaps the most divisive leader in recent Japanese history, infuriating liberals with his revisionist views of history and his dreams of military expansion. He was also the longest-serving and, by many estimations, the most influential.

For current Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, this complicated legacy will loom large as he considers taking up his mentor’s unachieved policy goals after a big win for their ruling Liberal Democratic Party in parliamentary elections Sunday, just days after Abe’s death.

Kishida has gained considerable political strength, riding a surge of emotion and vows of resilience from voters after the assassination, but he’s also lost the most powerful force in his party — Abe.

“Kishida now faces an increasingly murky political situation,” the liberal-leaning Asahi newspaper said in an editorial. “The death of Abe, who headed the largest LDP wing, will certainly change the party’s power balance.”

Kishida made his immediate priorities clear after the election: “Party unity is more important than anything else.”

But he must also make quick progress on growing worries over rising prices and a stagnant economy even as he tries to figure out how to boost Japan’s defense in the face of an aggressive China, Russia and North Korea.

And then there’s Abe’s polarizing nationalistic agenda, much of which was left unfinished, including his attempts to boost patriotism in schools, revoke the apologies made in the 1990s over Japanese aggression during the war and the controversial and divisive plan to revise Japan’s war-renouncing constitution to give the military more power.

How Kishida deals with Abe’s still considerable political presence may determine his success as a leader.

At the heart of Abe’s lingering influence — he left the top job in 2020 — is a paradox.

He alienated many in Japan, as well as war victims China and the Koreas, with his hawkish foreign and security policies, as well as his ultraconservative — sometimes revisionist — stance on the so-called history issues related to Japan’s wartime actions.

Abe pushed back against post-World War II treaties and the verdicts of the tribunal that judged Japanese war criminals and was a driving force in efforts to whitewash military atrocities and end apologies over the war.

The Japanese electorate, however, carried him to power in six elections. And his work to strengthen the alliance with the United States and to unify like-minded democracies as a counterweight to China’s assertiveness endeared him to U.S. and European elites.

His long grip on power even amid criticism over his more extreme views can be explained by voters’ desire for stability and an improved economy, Abe’s stranglehold on the conservative wing of his party and the haplessness of the opposition.

His first period as prime minister, which began in 2006, ended in failure after a year, partly because of a backlash to his nationalist policy goals.

After three years of opposition rule, a rare interruption in decades of LDP dominance, Abe returned to power with a landslide victory in 2012.

“After his first stint failed, he learned that his nationalistic agenda of building a ‘beautiful nation’ cannot move forward unless he has another agenda to balance it out, like two wheels of a cart,” said Koichi Nakano, a Sophia University professor of international politics.

While still chipping away at enacting his nationalist policies, Nakano said, Abe also began championing economic revitalization and compromised on issues such as promoting women’s advancement and accepting unskilled foreign labour to help boost a dwindling workforce — moves that allowed him to be seen as a realist.

He understood in his second term that “he needed to improve his narrative and policy focus on the economy. He convinced much of the public that ‘Abenomics’ was a necessary reform path,” said Leif-Eric Easley, a professor of international studies at Ewha Woman’s University in Seoul. Abe also “exercised institutional discipline over the government bureaucracy and his political party in ways that no opposition leader has yet been able to match.”

Abe was the grandson of right-wing former Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, which helped him win support from right-wing groups. He also was favoured by younger people, experts say, many of whom are more conservative than their counterparts in other parts of the world because of their deep interest in a steady economy so they can get work at major companies.

“It seems that voters preferred the stability Abe promised over the disorganized leadership that the (opposition party) provided” during its three years in power, said Jeffrey Hall, a professor at Kanda University of International Studies specializing in Japanese politics and nationalism. “To international observers, Abe’s support for historical revisionism looms larger than it did for domestic voters.”

While Abe’s eagerness to boost Japan’s military power was more than most Japanese citizens wanted, according to Easley, “he was right about Tokyo having to adjust to a challenging security environment that includes China, Russia and North Korea.”

Kishida enjoys something of a political mandate after Sunday’s election, and will likely be in office until scheduled elections in 2025. He has said he wants to explore ways to make more progress on Abe’s push for constitutional revision, but there’s no detail now about what, exactly, that means or how he’ll try to do it.

Changing the constitution is a top party platform that Kishida will not want to risk, according to Ryosuke Nishida, a sociology professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, so he may delay the effort until he can forge a compromise with rightwing party members on the best way to proceed.

“Abe was one of the strongest voices for constitutional revision and a more proactive security policy. Now that he is gone, others will try to fill his shoes, but it will be difficult,” Hall said.