As the US moves to withdraw its military from Afghanistan over the next five months, concerns are growing about one American who risks being left behind.

Mark Frerichs, a contractor from Lombard, Illinois, believed held for more than a year by the Taliban-affiliated Haqqani network, was not mentioned in President Joe Biden’s address on Afghanistan last week. Nor was the troop withdrawal, scheduled to be complete by September 11, conditioned on his release from custody, fueling concerns that the US could lose bargaining power to get Frerichs home once its military presence is removed from the country.

“Any leverage that we had, we’ve just now announced to the world and to the Taliban and the Haqqanis that we’re going to pull out. Not only is it our leverage, it’s our military capability to rescue him,” Representative Michael Waltz, a Florida Republican and Green Beret who served in Afghanistan, said in an interview with the Associated Press. “So it’s just utterly disheartening.”

The Biden administration has said it regards the return of hostages to be a top priority. Despite this, the fate of a single captive is unlikely to sway the broader policy interest in ending a 20-year war that began in response to the September 11, 2001, attacks. It’s not uncommon for detainee issues to be eclipsed by other foreign policy matters, as appeared to happen last week when the administration didn’t mention Russia’s detention of two Americans, even as it announced reasons for taking punitive action against Moscow.

Even so, for Frerichs’ family, the failure to make his return a factor in the withdrawal is a source of frustration, as is the fact that the Trump administration signed a peace deal in February 2020, just weeks after Frerichs vanished in Afghanistan while working on engineering projects in the country.

His sister, Charlene Cakora, said in a statement that the military withdrawal ‘puts a time stamp on Mark. We have 150 days to get him home or our leverage is gone’.

Frerichs’ home-state senators, Democrats Tammy Duckworth and Dick Durbin, had raised similar concerns in a letter earlier this year to Biden.

In an interview Monday, Duckworth said she’s been reassured by the administration that Frerichs has been part of the discussions and that officials are aware of his case. She said she spoke privately with Biden himself last Thursday, handing him a note with information about the case.

“He said he was very well aware and he asked me to also let the family know that he was aware and was on top of it,” Duckworth said.

The US has not disclosed much about Frerichs’ fate or status but confirmed Monday that it was in active negotiations with the Taliban.

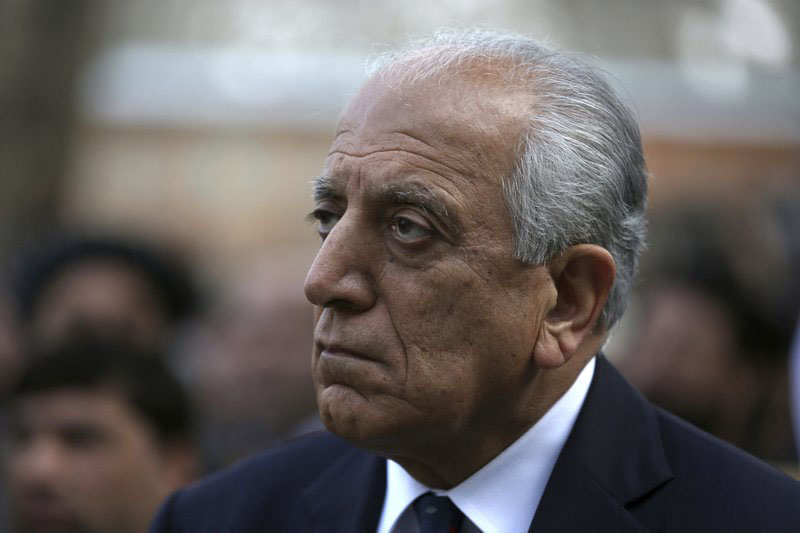

State Department spokesman Ned Price said in a statement that US peace envoy Zalmay Khalilzad, working closely with Roger Carstens, the special presidential envoy for hostage affairs, ‘has continued to press the Taliban for Mr Frerichs’ release, and continues to raise his status in senior-level engagements in Doha and Islamabad. We place a high priority on Mark Frerichs’ safety and will not stop working until he is safely returned to his family’.

The AP reported in January that the Taliban during the Trump administration had sought the release of a combatant imprisoned on drug charges in the US as part of a broader effort to resolve issues with Afghanistan. The request prompted dialogue between the State Department and the Justice Department about whether such a release could happen, though it ultimately did not.

Duckworth, who has spoken about the case with Khalilzad, said the Taliban remained ‘insistent’ on that release and not moved off that condition.

The announced withdrawal from Afghanistan was one of two significant foreign policy moves announced by Biden last week. The other involved sanctions on Russia for election interference and for the hack of federal government agencies.

The White House did not use that opportunity to call out Moscow for what US officials say is the unjust detention of at least two Americans: Paul Whelan, a corporate security executive from Michigan sentenced to 16 years in prison on espionage charges, and Trevor Reed, a Marine veteran who was convicted in an altercation with police in Russia and sentenced to nine years.

Whelan’s brother, David, said in a statement that he was hopeful for rapprochement between Moscow and Washington but also concerned that the tit-for-tat actions — Russia responded to the US sanctions with its own diplomatic sanctions — may have made that more challenging.

“First, the sanctions continue to make it difficult for the two nations to create the relationship and dialogue necessary to create conditions that might lead to Paul’s release,” Whelan wrote. “Second, the winnowing of US Embassy staff in Russia will make the difficult work of consular support even harder.”