Russia’s mercenary leader, Yevgeny Prigozhin, apparently died in a plane crash near Moscow on August 23. This was two months to the day after Prigozhin mounted a quasi-coup against Tsar Vladimir Putin, underscoring how this authoritarian leader was not going to allow a challenge to his reign to go unanswered.

Although Russia predictably denied culpability for bringing the private aircraft down, the Chinese government was even more circumspect. In a regular Foreign Ministry press conference the following day, spokesman Wang Wenbin simply stated, “We noted relevant reports.” When Prigozhin’s rebellion occurred, Beijing issued only a terse two-line statement, describing it as “Russia’s internal affair” but assuring Moscow of China’s support to “maintain its stability and achieve development and prosperity”.

This nasty episode will have underscored China’s belief that it must never rely on private mercenaries, and only on the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Political loyalty is paramount to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and the party views Russia’s overreliance on mercenaries as “getting caught in one’s own cocoon”.

For two decades, Putin nurtured private mercenaries such as Wagner Group, providing a counterweight to make sure his military generals did not get too big for their boots, as well as lending a veneer of deniability to Russia when they operated overseas in places like Syria or Libya.

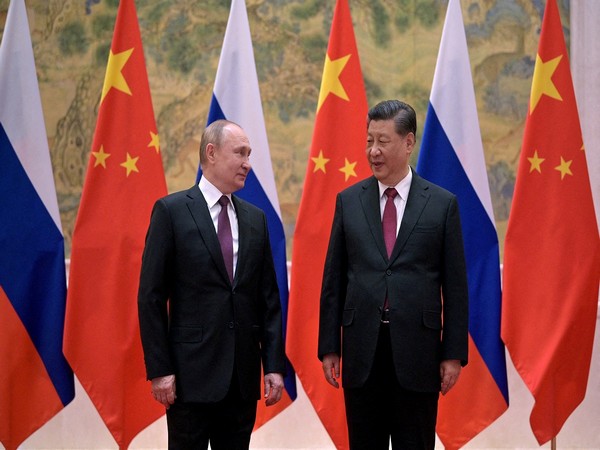

China and Russia share a “comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for the new era”. But surely the CCP must be asking tough questions about its “no limits” partnership, even if Russia is the only sizeable country that shares China’s disdain for the USA and the West. Yes, there are the likes of North Korea and Iran, but they are not in Russia’s league.

Russia’s war in Ukraine helps with China’s ideological campaign against the expansion of Western liberal ideas. However, perhaps Putin imbibed too much of Xi’s magic juice and became seduced by his assertion of the West’s inexorable decline. Xi and Putin likely thought the USA and NATO had become weary of war after 20 years in Afghanistan and Iraq, but now Putin is caught in a quagmire of his own against a neighbour just 1/28 th of Russia’s size.

Xi said in 2013: “Facts have repeatedly told us that Marx and Engels’ analysis of the basic contradictions of capitalist society is not outdated, nor is the historical materialist view of the inevitable demise of capitalism and the inevitable victory of socialism. This is the irreversible general trend of social and historical development, but the road is tortuous. The final demise of capitalism and the final victory of socialism must be a long historical process. We must have a very strong strategic determination, resolutely resist all kinds of erroneous propositions to abandon socialism, and consciously correct erroneous ideas that transcend the stage…to continuously win the initiative, advantages and gains for us.”

Xi’s ultimate goal, as enunciated above – to vanquish capitalism completely and to install socialism – has not altered one whit in the intervening decade. Because of such ideology, Western analysts should not be surprised that neither Putin nor Xi follow the “logic” of economic interests, or that they care much for the individual welfare of their subjects. Neither leader sees a lessening of repression at home or aggression abroad as being in their best interests.

Their meaningless talk of a “more just and fair world”, and of “a shared future”, are rhetorical words referring only to their own legacies. Against such ideology, peaceful coexistence with the rest of the world is going to prove increasingly impossible. Although Russia’s return to the “halcyon” days of the USSR is not feasible, China has no doubt about its own inexorable rise.

However, China does not have much of a choice. It cannot abandon Russia, for it would make a mockery of its fanfare about a new era. Apart from Putin, Xi does not have any other horse to back. Nor does it wish to see political chaos in Russia – a weak Kremlin is infinitely preferable to a political vacuum there. As a plus, Russia is still keeping the USA preoccupied in Europe, allowing China to advance its own military plans for Taiwan.

Michael Cunningham, a Research Fellow in The Heritage Foundation’s Asian Studies Center, noted that it is “overly simplistic” to think of American support for Ukraine against Russia as ultimately weakening China. He assessed: “The CCP hopes to emerge as the conflict’s greatest beneficiary, and it’s happy to let Russia, Ukraine and Ukraine arms suppliers – especially the United States – pay the tab.”

Weakening Russia is in the interests of the USA, even if China remains the long-term threat, and this is currently being done without threat to American military personnel. Cunningham noted, though: “Nevertheless, policymakers should have no illusions that their support for Ukraine will somehow inhibit China from challenging the global or regional order. The war may complicate some of Beijing’s short-term calculations, but

it’s helping to advance its longer-term agenda.”

Cunningham also refused to describe China and Russia as “allies”. Their partnership is based almost entirely on mutual opposition to American leadership and, “aside from this and a few other areas of shared interest, Beijing cares little about Moscow”. Currently, according to his own calculus, Xi has simply assessed that the benefits of supporting Moscow outweigh the costs.

China does not do alliances; in fact, its only ally is North Korea. “Beijing eschews any agreement that would put it on the hook for another country’s security interests, especially when that country is a rival great power that may someday become an adversary,” The Heritage Foundation academic explained.

Indeed, China and Russia have little in common. There is little mutual trust or respect, so it is not impossible that China will, one day, renounce its partnership with Russia and for their rivalry to overflow once more.

Cunningham followed this thought: “Thus, while Beijing might view Russia’s military setbacks – as well as the strengthening of US alliances in both Europe and the Indo-Pacific, which the war prompted – as a disadvantage in its struggle against American global leadership, it sees long-term benefits in a weakened Russia. Indeed, the weaker Russia’s military and economy become, the more it will become dependent on China, and the less of a threat it will pose in the future. The fact that China is reaping this benefit without having to fight Russia on the battlefield is doubly welcome in Beijing. It also doesn’t hurt that the US is depleting some of its own military resources by arming Ukraine.”

However, China does not particularly welcome the ongoing war or the possibility of escalation. Since it has no direct control over the conflict, it must therefore seize some advantage. This can be seen in its efforts to control the narrative, that it is neutral and an advocate of peace, and that the USA and NATO are warmongers by prolonging the conflict.

Of course, this is only spin, for China is heavily biased in favour of Putin. There are reported instances of Chinese material ending up in the hands of Russia’s military. In June, for example, Ukraine declared Chinese firms Hikvision and Dahua as “international sponsors of war” for supplying items like drones, thermal imagers, cameras and anti-drone guns. Neither firm has scruples, being heavily involved in equipping Beijing’s concentration camps in Xinjiang. Four other Chinese companies already on Ukraine’s naughty list are smartphone maker Xiaomi, radar company Comnav, construction firm CSEC and Great Wall Motor.

The US-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) identified three key weaknesses in the Sino-Russian partnership: historical and structural factors that engender strategic mistrust between Beijing and Moscow; Russian stagnation that renders Moscow a less useful partner and contributes to a growing power asymmetry; and Russian military aggression that sparks blowback for China and exacerbates Russia’s stagnation.

There is immense strategic mistrust between them. The Russian Empire took advantage of Chinese weakness during the “unequal treaties” (though the CCP is silent about this and blames only the West), while Russia is fearful of China encroaching upon its economic and strategic interests, and perhaps even their shared border. They are competing in Central Asia and the Arctic. Their current partnership is a notable deviation from history, with the normalization of relations only occurring in 1989. As the Chinese say, “One mountain cannot tolerate two tigers”, and Russia is increasingly the junior partner.

CSIS further noted: “China and Russia have long sought to cast themselves as equal partners, but this narrative is increasingly difficult to maintain given the growing power asymmetry between the two. As Russia stagnates or even declines, and as China continues to bolster its national power, Russia is poised to be a less useful partner to China in countering Western influence. China’s growing lead over Russia could also exacerbate existing tensions and mistrust between Beijing and Moscow if Russia feels it is being disrespected or treated as a junior partner.”

China’s economy is ten times the size of Russia’s, plus its per capita GDP surpassed Russia’s in 2020. In the same year, Russia accounted for just 2 per cent of China’s total trade, whereas China made up 18 per cent of Russian trade. Some two-thirds of that comprised oil, gas and coal. China spent 14 times more than Russia on research and development in 2020, so China’s technological advantage will continue to outpace Russia’s too.

Between 2014 and 2021, Russia’s defence budget remained essentially the same, whereas spending on the PLA grew by more than 47 per cent, emphasizing the growing imbalance between the partners.

CSIS added: “Compounding these issues is Russia’s persistent military aggression on the world stage. Russia’s numerous military interventions – especially its ongoing war in Ukraine – have created political and economic blowback for China. On top of that, Russia’s war in Ukraine has weakened Russia, diminishing its utility to China and further exacerbating the widening power gap between China and Russia.”

Russia is routinely prepared to use war to achieve its purposes, whereas China has been more restrained to date, at least in terms of overt invasions. Yet, Putin’s behaviour runs contrary to Beijing’s declared policy of non-interference in the affairs of others. Xi’s legitimization of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has already caused strong blowback against China internationally.

There is another significant advantage that China, as an outside observer, gains from the Ukraine war. Because the PLA seriously lacks any recent combat experience and has traditionally relied upon Russian weapons and doctrine, it is eagerly lapping up as much data as it can from the war. Publicly, Chinese analyses have not been as damning of Russian efforts as those in the West, but astute observations are being made.

For example, an article in the 12 January 2023 edition of the PLA Daily proclaimed that “the outcome of the land battlefield is still the key to the outcome of the war”. The PLA experienced a 55 per cent reduction in ground troops from 1997-2018, as the PLA Navy, Air Force and Rocket Force were prioritized. Some think the PLA might now be reassessing the wisdom of those soldier cuts.

The same PLA Daily report highlighted a lack of Russian manpower and shortcomings in joint combat. Specifically, battalion tactical groups have proved inadequate. “Deficiencies of the Russian battalion-level tactical groups have been exposed, such as their lacking the ability to be self-sustaining in combat and that they are too weak to be effective.” A proposed solution is to move from brigades back to divisions, which is interesting since the PLA itself has moved almost wholesale from divisions to a brigade structure. Russia is apparently planning to increase to two airborne divisions and five marine divisions. China, if it attempts to conquer Taiwan, would rely heavily on marines and airborne troops, so it may be tempted to do likewise.

The PLA ground force may use evidence from the Ukraine war to push for more resources and influence. One lesson is that high-intensity wars, which can look straightforward on paper, can quickly bog down. The longer Russia fails in Ukraine, perhaps the more chance there is that China will be dissuaded from attempting an ill-conceived invasion of Taiwan.

No matter, Xi remains convinced of his ultimate victory – “The final demise of capitalism and the final victory of socialism must be a long historical process.”