China appears to be moving faster toward a capability to launch its newer nuclear missiles from underground silos, possibly to improve its ability to respond promptly to a nuclear attack, according to an American expert who analysed satellite images of recent construction at a missile training area.

Hans Kristensen, a longtime watcher of US, Russian and Chinese nuclear forces, said the imagery suggests that China is seeking to counter what it may view as a growing threat from the United States. The US in recent years has pointed to China’s nuclear modernisation as a key justification for investing hundreds of billions of dollars in the coming two decades to build an all-new US nuclear arsenal.

There’s no indication the United States and China are headed toward armed conflict, let alone a nuclear one. But the Kristensen report comes at a time of heightened US-China tensions across a broad spectrum, from trade to national security. A stronger Chinese nuclear force could factor into US calculations for a military response to aggressive Chinese actions, such as in Taiwan or the South China Sea.

The Pentagon declined to comment on Kristensen’s analysis of the satellite imagery, but it said last summer in its annual report on Chinese military developments that Beijing intends to increase the peacetime readiness of its nuclear forces by putting more of them in underground silos and operating on a higher level of alert in which it could launch missiles upon warning of being under attack.

“The PRC’s nuclear weapons policy prioritizes the maintenance of a nuclear force able to survive a first strike and respond with sufficient strength to inflict unacceptable damage on an enemy,” the Pentagon report said.

More broadly, the Pentagon asserts that China is modernizing its nuclear forces as part of a wider effort to build a military by mid-century that is equal to, and in some respects superior to, the US military.

China’s nuclear arsenal, estimated by the US government to number in the low 200s, is dwarfed by those of the United States and Russia, which have thousands. The Pentagon predicts that the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Forces will at least double the size of its nuclear arsenal over the next 10 years, still leaving it with far fewer than the United States.

China does not publicly discuss the size or preparedness of its nuclear force beyond saying it would be used only in response to an attack. The United States, by contrast, does not rule out striking first, although President Joe Biden in the past has embraced removing that ambiguity by adopting a ‘no first use’ policy.

Kristensen, an analyst with the Federation of American Scientists, said the commercial satellite photos he acquired appear to show China late last year began construction of 11 underground silos at a vast missile training range near Jilantai in north-central China. Construction of five other silos began there earlier. In its public reports the Pentagon has not cited any specific number of missile silos at that training range.

These 16 silos identified by Kristensen would be in addition to the 18-20 that China now operates with an older intercontinental ballistic missile, the DF-5.

“It should be pointed out that even if China doubles or triples the number of ICBM silos, it would only constitute a fraction of the number of ICBM silos operated by the United States and Russia,” Kristensen wrote on his Federation of American Scientists’ blog. “The US Air Force has 450 silos, of which 400 are loaded. Russia has about 130 operational silos.”

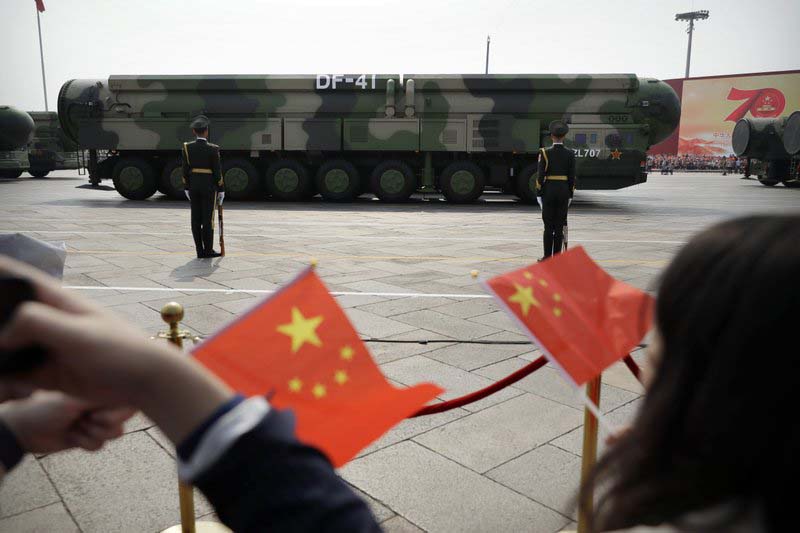

Nearly all of the new silos detected by Kristensen appear designed to accommodate China’s newer-generation DF-41 ICBM, which is built with a solid-fuel component that allows the operator to more quickly prepare the missile for launch, compared to the DF-5’s more time-consuming liquid-fuel system. The DF-41 can target Alaska and much of the continental United States.

China already has a rail- and road-mobile version of the DF-41 missile.

“They’re trying to build up the survivability of their force,” by developing silo basing for their advanced missiles, Kristensen said in an interview. “It raises some questions about this fine line in nuclear strategy,” between deterring a US adversary by threatening its highly valued nuclear forces and pushing the adversary into taking countermeasures that makes its force more capable and dangerous.

“How do you get out of that vicious cycle?” Kristensen asked.

Frank Rose, a State Department arms control official during the Obama administration, said recently there is little prospect of getting China to join an international negotiation to limit nuclear weapons. The Trump administration tried that but failed, and Rose sees no reason to think that will change anytime soon.

“They’re not going to do it out of the goodness of their heart,” he said, but they might be interested in talking if the United States were willing to consider Chinese concerns about related issues like US missile defences.

Rose says China’s main interest is in building up its non-nuclear force of shorter- and intermediate-range missiles, which, combined with a cyberattack capability and systems for damaging or destroying US satellites, could push the United States out of the western Pacific. This would complicate any effort by the United States to intervene in the event Beijing decided to use force against Taiwan, the semi-autonomous democracy that Beijing views as a renegade province that must eventually return to the communist fold.