When Bill Clinton spoke of how to build a bridge to the 21st century, it was to be constructed with balanced budgets, welfare recipients who found jobs and expanded global trade.

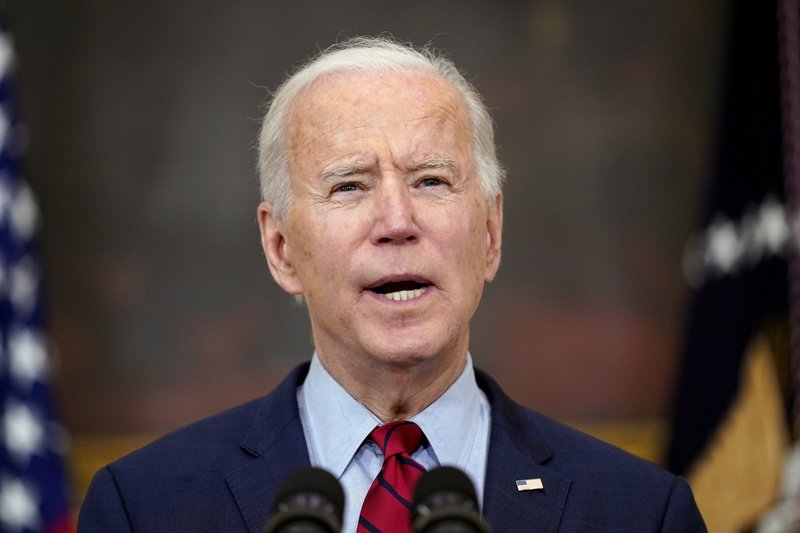

Three decades later, President Joe Biden is dealing with harsh 21st century realities and his approach has been the exact opposite: Borrow to spur growth, offer government aid without mandating work and bring global supply chains back to the United States.

This change in Democratic policy reflects the unique crises caused by the pandemic, as well as decades-old trends such as the rise of economic inequality, the downward slope of interest rates that made borrowing easier and globalization’s pitfalls as factories departed the Midwest. White House aides are comparing the scope of Biden’s policy ambitions to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s after the Great Depression.

All of these factors coalesced in Biden’s $1.9 trillion relief package that his administration is now selling nationwide to voters. And even grander designs are still to come for an infrastructure package and investments in workers that Biden will probably detail in a speech Wednesday in Pittsburgh.

“The underlying goal of how do we deepen, broaden and secure America’s middle class has changed with the times,” says Heather Boushey, a member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers. “What happened in 2020 was this huge unmasking of all these fragilities and vulnerabilities in our economy.”

Biden’s relief package — which comes on top of roughly $4 trillion in aid already approved to address the coronavirus fallout — is an effort to strengthen the social safety net that many in his own administration had helped stitch during Clinton’s second term.

White House chief of staff Ron Klain held the same job for Clinton’s vice president, Al Gore. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen was Clinton’s chief economist. Gene Sperling, who oversees the release of the relief money, was director of the National Economic Council back then. Deputy chief of staff Bruce Reed had been the head of Clinton’s Domestic Policy Council.

At the time, the Clinton administration seemed to have found a winning formula. The 1996 welfare overhaul signed during the heat of a reelection campaign was designed to end welfare as an entitlement and move aid recipients into jobs, while globalization offered the potential for greater profits for employers.

“We begin a new century, full of enormous possibilities,” Clinton said as he accepted the Democratic nomination that year in his “Bridge to the 21st Century” speech. “We have to give the American people the tools they need to make the most of their God-given potential. We must make the basic bargain of opportunity and responsibility available to all Americans, not just a few.”

The U.S. economy seemed solid after Clinton’s reelection. Record highs were set in the percentage of Americans working. The federal budget was running a $236 billion surplus by 2000. U.S. companies could reach new markets through trade pacts and China’s admission into the World Trade Organization.

But the stock bubble in internet companies burst as the Clinton era ended. Factories quickly relocated to China, while assistance meant to retrain the newly unemployed never fully delivered as intended. The seeds of inequality became apparent after home prices inflated in the ensuing years and then plunged, causing a financial crisis in 2008 followed by a grindingly slow recovery.

Democratic voters have also evolved since the peak of Clintonism in the 1990s. They became more diverse, more likely to hold a college degree and more likely to live in an affluent city or suburb. That progression was easily overlooked until Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016 on the promise of scrapping trade deals, declaring that the government had stiffed the public and vowing to return the country to a past blue-collar identity.

“That happened without Democrats really taking it into their politics until Trump comes along and he is the wakeup call,” said Elaine Kamarck, a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution who served in the Clinton White House. “Democrats were slow to realize this, but Biden was not. Biden was probably the best about this.”

Celinda Lake conducted polling for both the Clinton and Biden campaigns. Clinton was a relatively young 46 when he became president, the first baby boomer to take the reins of national leadership. Baby boomers, by contrast, had practically grown up with Biden in one office or another. An experienced hand in a crisis, he spent 36 years in the Senate and eight as vice president to Barack Obama.

“It was the inverse choice in terms of leadership — in 1992, they went for the next generation, the new thing,” Lake said. “In 2020, they went for the steady leader.”

At 78 years old, Biden can remember an older Democratic Party that believed big government was not inherently bad government. The child tax credits in his relief package let aid flow to families without imposing work requirements. His $1,400 direct checks go to each partner in a couple earning as much as $150,000, effectively expanding the social safety net beyond the poor to 158.5 million households.

The pandemic relief is financed entirely by debt, something made possible by interest rates hovering near historic lows. Despite the growth of the national debt since Clinton’s presidency, the federal government spent a smaller share of gross domestic product servicing the debt last year than during the Clinton era. This has made it possible so far for the government to borrow such large sums, though long-term debt pressures remain.

The Biden administration is now challenging China, which never embraced the values of democracy as trade advocates once believed it would. The White House has made it a priority to ensure the United States has a steady supply of vital goods such as computer chips, a sector increasingly dominated by China. A chip shortage is stifling auto production around the world, making it a threat to U.S. manufacturing jobs.

Robert Lawrence, a Harvard University professor who served on Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers, doubts that the factory jobs can all return as automation has reshaped the economy. But he sees the Biden administration as pursuing new policies to help workers.

“If you think about Biden, we’re going back to big government and we’re going back to a new form of welfare — which includes the middle class,” Lawrence said. “These are really revolutionary changes.”

Al From, founder and former CEO of the centrist Democratic Leadership Council, said the Clinton era was also about helping workers and reflected that moment when welfare had created dependency and investors saw the U.S. debt as excessive. Even if Biden’s policies seem to break with that era, the values are the same.

“You have policies that are trying to achieve the same goals,” From said. “They may be different, but they’re consistent with the long-term principles of the Democratic Party.”