A prospective juror who once lived in the neighborhood where George Floyd was arrested told the attorney for an ex-officer charged in Floyd’s death that he had a personal reason for wanting to serve on the jury.

“Because me, as a Black man, you see a lot of Black people get killed and no one’s held accountable for it, and you wonder why or what was the decisions,” Juror No. 76 said under questioning during jury selection in Derek Chauvin’s murder trial. “So, with this, maybe I’ll be in the room to know why.”

But the man won’t be in the room. Even though he said he felt he could weigh the evidence fairly, he was struck by the defense. It was an illustration of how difficult it can be for people who say they have personal experience with police misconduct to make it onto juries that hold them accountable.

“We have a Black man who was probably in the best position to judge the case being excluded,” said Nekima Levy Armstrong, a civil rights attorney and head of a community activism organization called Wayfinder Foundation.

The man said he experiences daily racism, and he strongly agreed that police are more likely to respond with force on Black people than on white people. Levy Armstrong called the juror’s exclusion a “huge slap in the face” that “just underscores why people believe there is systemic racism at work within these judicial processes.”

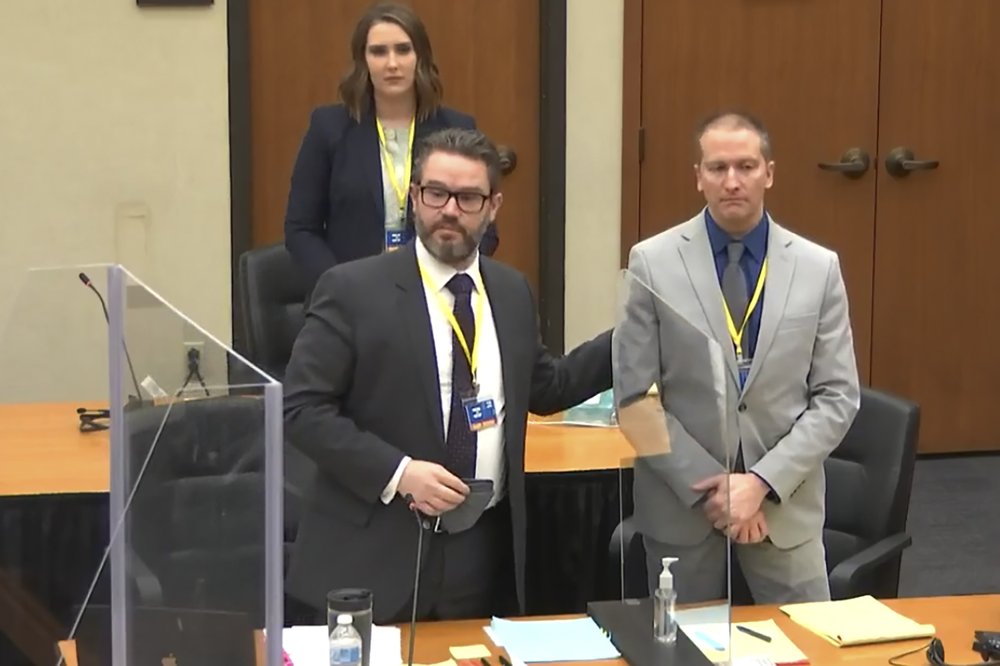

Jury selection in Chauvin’s case is nearly complete, with 12 of 14 required jurors selected by Thursday. So far, the racial makeup of the jury is evenly split; six of the jurors are white, four are Black, and two are multiracial, according to the court.

Floyd was declared dead last May after Chauvin, who is white, pressed his knee against the Black man’s neck for around nine minutes while he was face-down on the ground and handcuffed. Floyd pleaded for air several times and eventually grew still.

But local activists like Levy Armstrong say that police brutality was rampant long before Floyd’s death.

Juror 76 — they are being referred to in court only by number to protect anonymity — said Minneapolis police would “ride through the neighborhood with ‘Another One Bites the Dust’” after a local person was shot or arrested.

Levy Armstrong said such context would be essential to the group of 12 people deciding Chauvin’s fate. Local activists have noted that several selected jurors have relationships with police officers, and wondered: Why can’t a Black man who has had negative experiences with police make it on a jury?

Nelson used one of his peremptory strikes to dismiss the man, after trying and failing to have him struck “for cause” — citing his negative opinion of Minneapolis police and his statements that Floyd was “murdered.”

Prosecutors argued against striking for cause, saying the man was simply reflecting on the reality of his experience, and pointed out he had said he could set his personal feelings aside.

Nelson’s peremptory strike, which was not challenged, did not require an explanation. Attorneys cannot strike a juror based on race.

Hennepin County Judge Peter Cahill said he didn’t think a challenge would have worked in this case, citing the man’s negative statements about the Minneapolis Police Department.

But he noted the man’s statements also showed he could be fair.

“My inference from what he said is, ‘I can put it aside, and if he is not guilty, I can reach that verdict because I feel comfortable telling people why it happened,’” Cahill said, adding that “would put him right in the middle as far as fair and impartial.”

Alan Turkheimer, a Chicago-based jury consultant, said he was not surprised the defense would try to keep someone who experienced police brutality off a jury.

“Sometimes people just can’t be fair, even if they don’t know it,” he said. “It’s so ingrained. It’s so hard to shake something like that.”

He added that questioning — and ultimately striking — prospective jurors based on their experiences provides a “built-in advantage for police officers.”

During racial justice rallies this week, many have turned their attention to systemic racism within the justice system and how juries are selected, said Jaylani Hussein, a local activist and executive director of the Minnesota chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations.

“It’s a horrible, racist thought process: We have to stop people who may get angry — you know the angry Black man or angry Black woman — from getting into the jury because they won’t take this seriously,” he said.

For the juror, the idea of being a part of forming Chauvin’s verdict was something he approached as a weighty matter. He said he had avoided watching in-depth news coverage of Floyd’s death, even steering clear of the subject with his wife.

“I didn’t form an opinion on Mr. Chauvin because I didn’t know him,” the juror said. “It’s sad. It’s another Black man being murdered in police hands. That’s all I could say.”