The findings of new research suggest that squeezing through tight spaces makes cancer cells more aggressive and helps them evade cell death.

The findings, published in ‘eLife’, reveal how mechanical stress makes cancer cells more likely to spread, or metastasize. While metastasis is the cause of most cancer deaths, there are currently no available cures. However, the new results may help scientists develop novel approaches to treat or prevent metastasis.

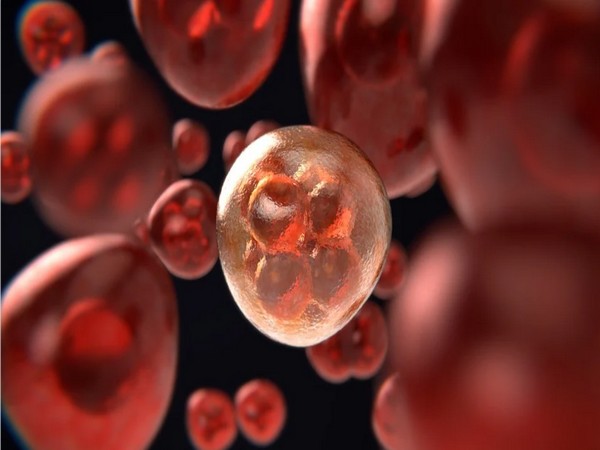

It can be a tight squeeze for cancer cells to escape their tumor or enter tiny blood vessels, called capillaries, to spread through the body. The cells must collapse and change their shape to do this, in a process called confined migration. As they spread, the cells must also avoid detection and destruction by the immune system.

“Mechanical stress can cause cancer cell mutations, as well as an uncontrolled increase in cell numbers and greater tissue invasion,” explains first author Deborah Fanfone, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Cancer Research Center of Lyon, France. “We wanted to know if the mechanical stress of confined migration makes cancer cells more likely to metastasize, and how this happens.”

To answer these questions, Fanfone and colleagues forced human breast cancer cells through a membrane with tiny, three-micrometer-sized holes to simulate a confined migration environment. After just one passage through the membrane, they found that the cells became more mobile and resistant to anoikis – a form of programmed cell death that occurs when cells become detached from the surrounding network of proteins and other molecules that support them (the extracellular matrix). The cells were also able to escape destruction by immune natural killer cells.

Further experiments showed that increased expression of inhibitory-of-apoptosis proteins (IAPs) increased the resistance of cancer cells to anoikis. Treating the cancer cells with a new type of cancer drug called a SMAC mimetic, which degrades IAPs, removed this protection.

The team then studied how breast cancer cells that had undergone confined migration behave when administered to immune-suppressed mice. They found these mice developed more lung metastases than mice that were administered with breast cancer cells that had not been exposed to confined migration.

“By mimicking confined migration, we’ve been able to explore its multifaceted effects on cancer aggressiveness,” says senior author Gabriel Ichim, who leads the Cancer Cell Death team at the Cancer Research Center of Lyon. “We’ve shown how the process boosts survival in cancer cells and makes them more prone to forming deadly metastases.”

The authors add that these results may lead to additional studies of potential metastasis treatments, such as therapies that soften tumors to reduce mechanical stress on cancer cells, or that block IAPs. These include SMAC mimetics, which are currently being tested in clinical trials as a possible new treatment approach.