According to a study co-led by researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine, NewYork-Presbyterian, the New York Genome Center, Harvard Medical School, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, a typical, spontaneous mutation in blood stem cells, which has been linked to higher risks of blood cancer and cardiovascular disease, may promote these diseases by altering the stem cells’ programming of gene activity and the variety of blood cells they produce.

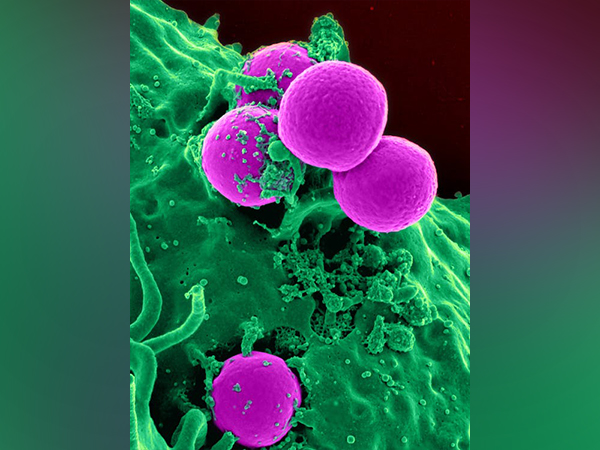

A significant population of circulating blood cells with the DNMT3A R882 mutation, also present in blood stem cells, grows as a result of the blood stem cell mutation. These mutant outgrowths are regarded to constitute a very early, pre-malignant stage of cancer formation, and they tend to become more prevalent as people age. Since the mutant cells generally have the same appearance and functionality as normal cells, it has been difficult to determine the exact molecular specifics of how they develop. The researchers overcame this obstacle in the study, which was published on September 22 in Nature Genetics, to shed light on the implications of R882 mutations in DNMT3A, the gene that is most frequently altered in blood cells.

The study’s senior author, Dr. Dan Landau, an associate professor of medicine in the Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, an associate professor of physiology and biophysics, and a member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine, said, “These findings help us understand how these mutated cells outgrow normal cells and pave the way for possible future interventions targeting these cells to prevent cancers and other clonal outgrowth-related conditions.”

Dr Irene Ghobrial, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, and Dr Landau’s lab worked together on the project. Blood cell clonal outgrowths are quite prevalent in multiple myeloma patients, according to Dr Ghobrial’s team, who provided samples of blood stem cells from their marrow.

In order to identify the DNMT3A R882 mutation and the map gene activity and chemical marks on DNA known as methylations, programming marks that turn off neighbouring genes, Dr Landau’s team examined more than 6,000 cells from the patients. They were able to capture the differences between the blood stem cells with mutations and their healthy counterparts in previously unheard-of detail.

The scientists discovered, for instance, that patients with clonal outgrowths in their blood had a higher risk of cardiovascular disease because the mutant stem cells produced mature blood cells that were skewed toward red blood cells and the cells that produce blood-clotting platelets.

A methyltransferase, which aids in adding methylations to DNA, is typically produced by the gene DNMT3A. The absence of these “off switches” across the genome and the anomalous activation of important genes were caused by the mutation’s disruption of regular methylation, the researchers discovered. The latter contained genes that promote inflammation as well as cancer-associated growth genes, which is consistent with the mutant cells’ advantage in growth and survival as well as a higher chance of developing cancer.

According to study co-first author Dr. Anna Nam, assistant professor of pathology and laboratory medicine in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, a member of the Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine, and a pathologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, “our hope is that by identifying molecular signatures like these we’ll be able to target these clonal outgrowths and prevent cancer development in people who are still healthy.”

The study of clonal outgrowths caused by additional mutations will continue, according to the researchers. In order to accelerate and expand the scope of these investigations, they are also developing their multi-omics methodologies.

“We should soon be able to undertake studies of many more cells at a time, providing us a full view of what’s going on,” said Neville Dusaj, co-first author and a student in the Landau lab’s Tri-institutional MD-PhD Program.